Experiments

I built a design portfolio in 12 months with zero formal training

Dec 10, 2025

What self-teaching revealed that formal education might have hidden.

This is part 1 of a 2-part series on building an industrial design portfolio without formal training.

When I first started considering switching into industrial design, I started my research in breaking into the industry on Reddit. Hoping to get some understanding of what options I had before jumping right into school, I found a large body of questions and answers that can all be summarized by this post:

Where do I start in Industrial design without a degree?

You don’t.

There’s plenty of juniors right now out of work and struggling to find work. We don’t need one more person who is not qualified to jump in the job search. Sorry to be so blunt.

If you want to get into ID, spend some time (a year +) building up a portfolio and learning all of the core skills you’ll need; get an internship, then proceed from there. (This will take several years, and at least 2 years to get a firm understanding of CAD modeling for design).

As discouraging as this was, after a year down this path I now have a completed portfolio, confidence in my foundation skills, and I’ve landed interviews for ID internships at top design firms in NYC. The internship might still take years and I’m still considering school because this truly is not an easy industry to break into. But since we are a year in, I thought I’d share what it has looked like so far.

The Unexpected Gift of Going Solo

Without a curriculum dictating my path, I had to figure out who I was as a designer on my own. Without anyone making decisions for me, I could think deeply about what interested me and where to explore. From that I avoided the major pitfall most college students fall into: a portfolio that screams “I did this because I was told to.” Having attended college before, I know this is mostly a result of being told to do so many things with so little time to find intention in what you are doing. I’m grateful that this method gave me space to evaluate how and where I fit into the industrial design world.

Without constant deadlines, time spent became a compass instead of a source of stress. Whatever held my undivided attention the longest revealed what I actually cared about. As a result, advanced surfacing appears throughout my portfolio. I discovered I loved it early on, and without deadlines, I could stop mid-project to improve my skills whenever my taste outpaced my ability.

This year gave me valuable insights. Even if I eventually attend design school, I’ll be a different kind of student. I know my strengths, my interests, and what I need from a program. In a field where education doesn’t guarantee employment, I believe that initial self-exploration is worth the detour.

While the act of portfolio building brought me many joys and insights, the process itself was not intuitive. The gap between knowing what you want to portray and executing that in a concise format is vast, especially without institutional guidance.

The Hardest Step: Understanding What Actually Matters

A while back I was reflecting on my college experience learning electric circuits, embedded systems, and computer architecture. These subjects are largely interconnected but university splits them into digestible scopes taught in isolation. So I trudged through these concepts without connecting them until the very end, painfully learning every single distant concept until finally reaching a complete understanding of my major. I realized my experience was essentially like assembling a puzzle without the photo on the box. Only after you build the whole thing and look at it do the steps you chose at the beginning finally make sense. Only then can you execute them with intention.

This mirrors how I learned sketching, modeling, and prototyping in isolation. So when approaching my first start-to-finish industrial design project without a thesis professor, I didn’t know how those skills worked in unison. I didn’t understand the process of invention, how to navigate layers of endless questions, or where to find my next move in the mess of ideas. While discovering the process of creating, I was also trying to build a portfolio piece that communicated I knew what I was doing. I looked at other designers’ work online, trying to reverse-engineer what made them good. I had examples of renders and process shots but little guidance on how to visually explain my thought process. I was swimming in examples with no ability to evaluate what mattered. The growing ambiguity resulted in stalling.

For 4.5 months I made no progress on my portfolio.

“When faced with a difficult problem, don’t try to solve it. Instead, make sure you understand it. If you understand it properly, the solution will be obvious.”

But applying that to a problem as hard as learning a whole career, observing the problem in full becomes impossible. The context is too vast. You can’t see what the industry values, why certain choices matter, or how the pieces fit together when you don’t have the map.

I needed someone who had already figured out the image on the puzzle box. Ideally, they’d built as many puzzles as possible without the box and analyzed the patterns. Even better if they’d watched many others build the puzzle and learned how to course correct early.

I’d taken Offsite’s student program before and found that the instructors consistently compressed years of trial and error into a single actionable insight. When they announced a portfolio bootcamp, taught by Reid Schlegel, meant to revamp an existing project, I signed up even though I only had sketches and some failed 3D modeling attempts.

The 10-week syllabus consisted of one portfolio section per week: resume, research, moodboards, sketching, prototyping, renders. For each section I absorbed good and bad examples, processed Reid’s insights into core takeaways, applied those learnings to my project, built a layout communicating the process, and addressed last week’s feedback. Three industry hiring managers would review the final piece at the end. The pressure was on and the work was nonstop, but all problems contributing to my lack of progress vanished.

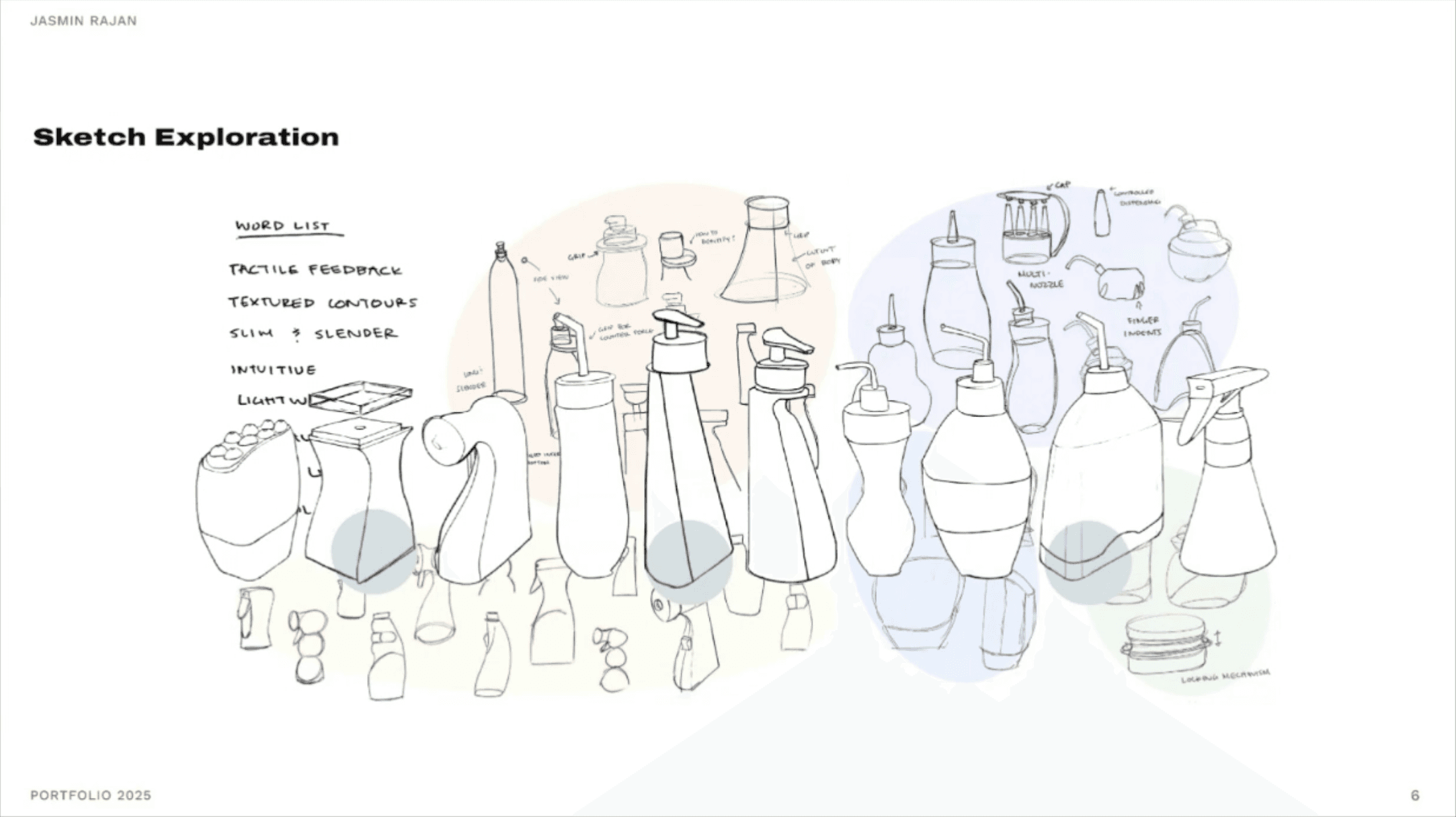

You can see my understanding develop in the evolution of my sketch page. From his initial lecture I landed here:

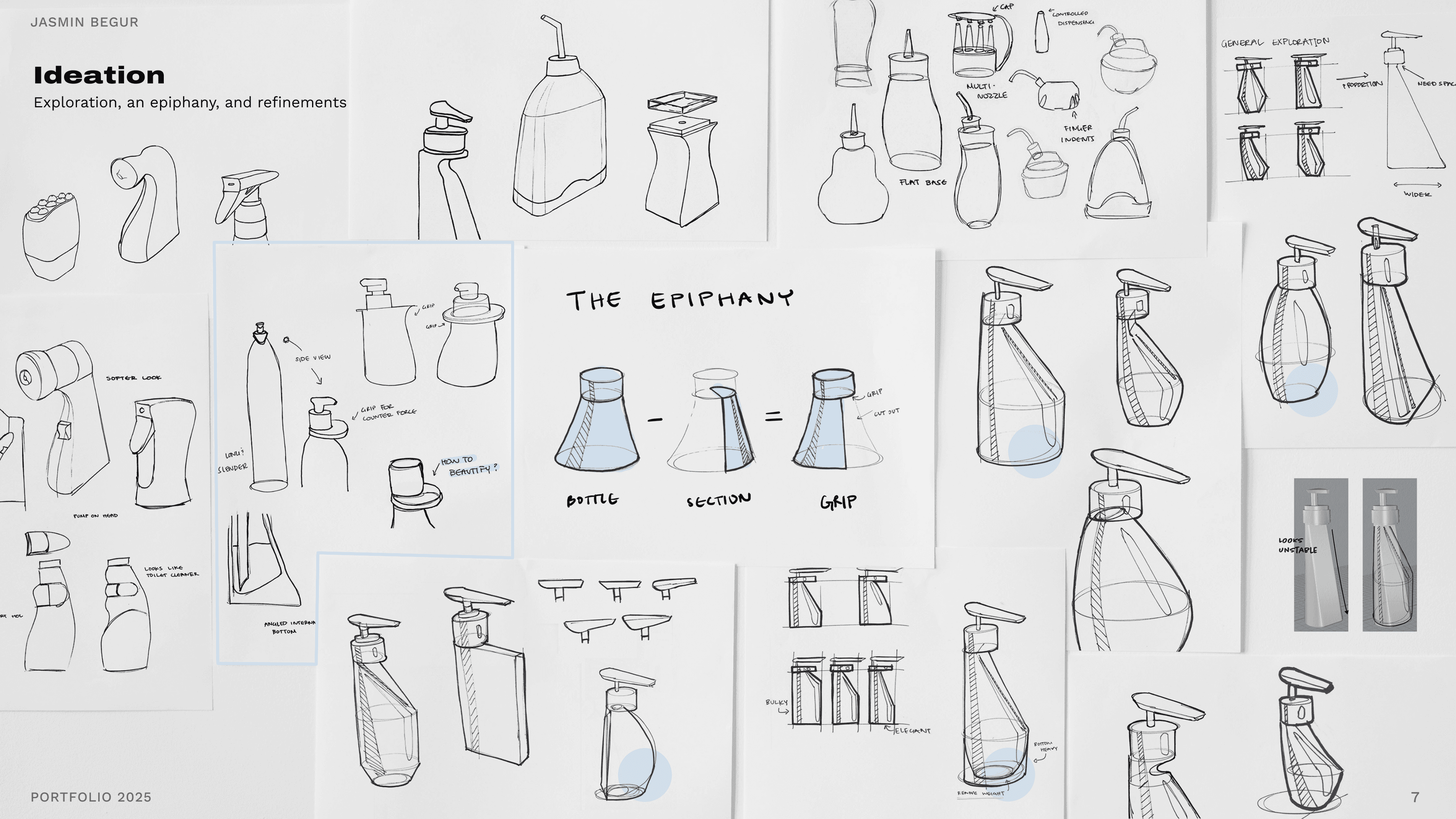

I knew the pump highlighted in the middle was my next page but I had so much to communicate that I lost track of its importance. Reid quickly pointed this out in his feedback:

“I see that you did a lot of exploration but it’s important to communicate how you decided on a specific idea. Try to go a layer deeper on what you are wanting us to look at here to get to the next step”

My next attempt honed in on what I actually learned from sketching:

And week by week this continued. In 10 weeks I gained a thorough understanding of what matters in ID projects, why it mattered, effective visual communication methods, and ultimately my first “completed” portfolio piece.

Completion was a big step but it wasn’t what gave this class value. Plenty of people finish projects that don’t get them hired. What Reid did was show me where my understanding had gaps I couldn’t see. He could see the complete picture, so he knew exactly where I’d gone blind. His knack for using his complete understanding to provide thorough, accurate feedback will forever guide my understanding of the context I need to challenge myself independently. I learned the value of attempting guided risks paired with early intervention.

There’s a reason this worked so well. Psychologist Lev Vygotsky spent his career studying how people master complex skills and discovered what he called the Zone of Proximal Development, the sweet spot between what you can do alone and what you can achieve with expert guidance. His research showed that we learn complex skills fastest not through passive instruction, but by attempting things just beyond our current ability while getting immediate expert feedback.

Taking this further: learning how to extract knowledge from people who understand the system becomes the skill itself.

In coursework, that means understanding what the assignment is trying to teach you. Submitting unrelated work is a disservice to understanding what the experts are prioritizing and a missed opportunity for focused feedback. It means observing the constraints to choose an intention, then providing that context during feedback so others can pinpoint where you went off path. It means being open to being told you’re wrong without taking it personally.

Completing my first studio project, start to finish, was a momentous step in becoming an industrial designer. While it couldn’t have been done without the sketching lessons, advanced surfacing tutorials, 3D printing experimentation, and rendering skills, it wouldn’t be what it is today without the guidance, feedback, and care from those who helped me push past what I could achieve as a beginner.

Knowing what matters and actually executing it in a portfolio are different challenges entirely. In Part 2, I’ll break down the specific strategies I used to choose projects, develop my voice, and make every piece count in those critical three seconds a hiring manager spends looking at your work.

Check out the project I completed here!

Comments